Pedro F. Gouveia, Rogélio Luna, Francisco Fontes, David Pinto, Carlos Mavioso, João Anacleto, Rafaela Timóteo, João Santinha, Tiago Marques, Fátima Cardoso, Maria João Cardoso

KEYWORDS

Breast cancer · Augmented reality · Remote telementoring · Surgical education

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Augmented reality (AR) has demonstrated a potentially wide range of benefits and educational applications in the virtual health ecosystem. The concept of realtime data acquisition, machine learning-aided processing, and visualization is a foreseen ambition to leverage AR applications in the healthcare sector. This breakthrough with immersive technologies like AR, mixed reality, virtual reality, or extended reality will hopefully initiate a new surgical era: that of the use of the so-called surgical metaverse. Methods: This paper focuses on the future use of AR in breast surgery education describing two potential applications (surgical remote telementoring and impalpable breast cancer localization using AR), along with the technical needs to make it possible. Conclusion: Surgical telementoring and impalpable tumors noninvasive localization are two examples that can have success in the future provided the improvements in both data transformation and infrastructures are capable to overcome the current challenges and limitations.

INTRODUCTION

Augmented reality (AR) is an interactive experience in a real-world environment, where the seen objects are enhanced by visual and nonvisual computer-generated information [1]. The major outbreak to fully disseminate AR technology was the creation of handheld devices. In 2013, Google announced its open beta Google Glasses, and, in 2015, Microsoft announced its AR headset (HoloLens). In the following year, AR entered the mainstream map with the tremendous success of Pok.mon Go (a mobile game by Niantic and Nintendo). Regarding healthcare settings, AR has demonstrated a potentially wide range of benefits and educational applications [2, 3]. The concept of real-time data acquisition, machine learning aided processing, and visualization is a foreseen ambition to leverage AR applications in the healthcare sector [4].

This breakthrough with immersive technologies like AR, mixed reality (MR), virtual reality (VR), or extended reality (XR) will hopefully initiate a new surgical era: that of the use of the so-called surgical metaverse. The metaverse is defined as Internet access via AR/VR/MR/XR, through a headset, and is already considered to be the next-generation mobile computing platform [5]. This ability is highly relevant during surgery because the surgeon is fully sterilized with surgical gloves and unable to easily access medical data through electronic medical records or medical images stored in the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS).

Virtual health has been heralded as the “next big thing” in healthcare. Defined as telehealth, digital therapeutics, and care navigation via remote technologies, virtual health promises several benefits, including new medical education methods [6]. Remote telementoring is a branch of telehealth, and one of the applications of AR in healthcare inside the operating room, providing real-time supervision and technical assistance during a surgical procedure by a remote expert surgeon [7]. It can help to make practical surgical education available worldwide by reducing travel costs, distance, and time constraints. Recent research concluded that there is no difference in skill acquisition or knowledge retention when compared to traditional on-site mentoring [8]. In this paper, we will focus on the future use of AR in breast surgery education describing two potential applications (surgical remote telementoring and impalpable breast cancer [BC] localization using AR) and the technical needs to make it possible.

METHODS

Surgical Remote Telementoring

To evaluate the feasibility of remote telementoring in BC surgery, a trial took place between the Champalimaud Foundation, in Lisbon, and the University of Zaragoza, in Spain. A dedicated 5G network provided indirect connectivity (USB tethering via 5G smartphone) to the doctor’s Microsoft HoloLens 2®. From an end-to–end perspective, a communication channel was established through the 5G private network, the local corporate network (Lisbon, Portugal), the Internet, and finally the public 5G network, at the other end (Zaragoza, Spain).

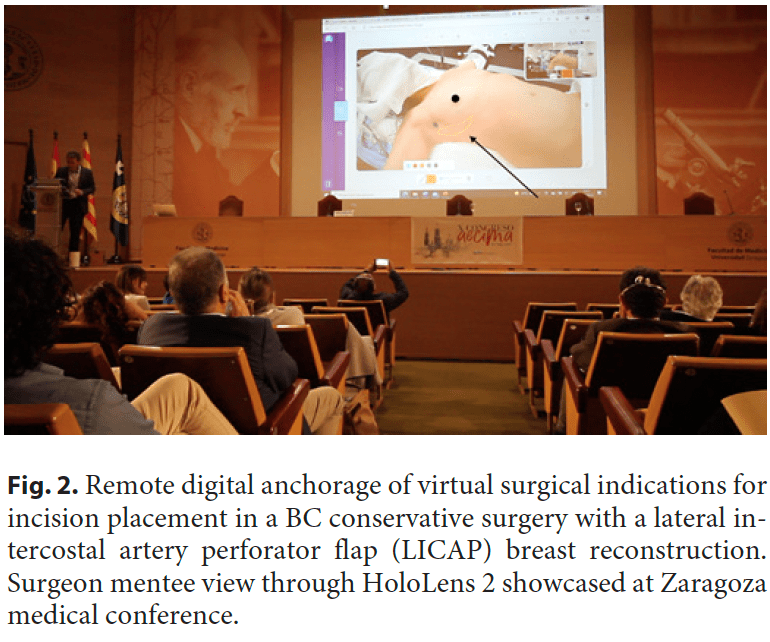

The surgeon mentor with a laptop computer in Zaragoza was linked to the local surgeon mentee in Lisbon using a HoloLens 2 headset with a dedicated communication software by Remaid® and the connection described. The “remote mentor surgeon” in Zaragoza, in spite of the considerable physical distance between the two, was able to assist the “performing mentee surgeon” (Fig. 1) in his delicate task in the operating room as if he was physically in the operating rooms. This feature was only achievable thanks to AR, implemented using an AR headset, and 5G connectivity. More broadly, AR in the operating room allows the surgeon to interact within an AR view, with computer-generated images blending with the real patient, where digital content is properly displayed without impairing visibility. In the presented use case, two distant surgeons were synchronized through video and sound with reduced latency thanks to the latest and most powerful broadband technology for transmitting digital information: a private 5G network. However, this was not an ordinary videoconference. More than that, advanced computer graphics enabled an AR world within a live surgery, meaning that the remote surgeon was able to anchor virtual objects like a surgical indication for incision placement (Fig. 2) during a BC conservative surgery with a lateral intercostal artery perforator flap [9] breast reconstruction. Moreover, comments about the surgical technique and anatomic structures identification from the remote expert were enabled through this immersive setup. Since this case was only a proof-of-concept experience, we still need to validate these immersive methodologies in breast surgical education and demonstrate their use when compared to the current standard teaching methodologies. It is expected that immersive technologies can help to introduce the metaverse in post-graduate surgical education.

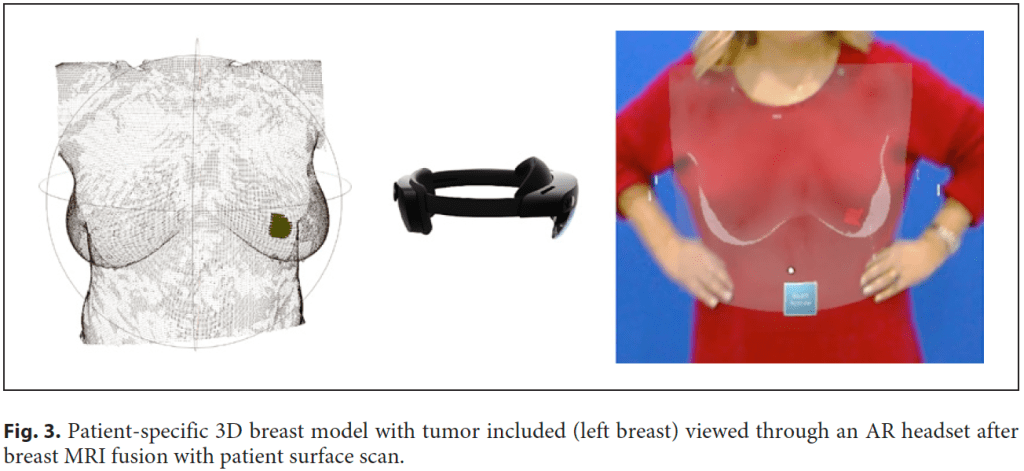

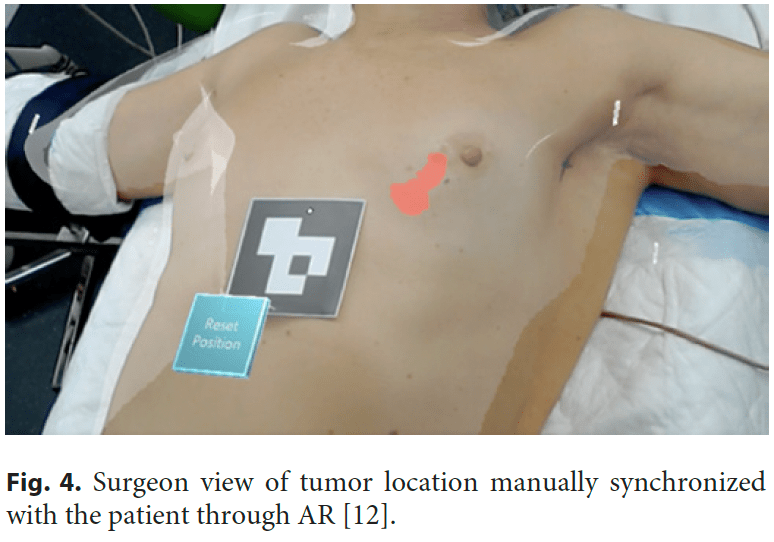

BC Localization with AR

Another possible use of AR in breast surgery, this time with the help of advanced computer vision tools, is to track real-life objects in an augmented space visualization, making this technology suitable for developing AI-assisted guidance systems in surgical scenarios [10–12]. Currently, in the presence of impalpable tumors, surgeons need to take into account multiple different imaging exams (like mammograms, ultrasound, or breast magnetic image resonance) to “mentally” visualize and localize the cancer that will be removed during surgery [13]. Radiological images and written medical reports are gathered to perform surgical treatment planning, and surgeons are required to have the mental load to achieve a cognitive medical image fusion regarding tumor location and size. This is specifically challenging in BC because not only the majority of patients are candidates for BC conservative treatment, but also because due to screening and neoadjuvant treatments, lesions tend to be smaller and frequently impalpable. Invasive techniques are currently used to localize these lesions, like wire-guided [14], clips [15], carbon tattooing [16], magnetic seeds [17], or radioactive technetium (99mTc) [18]. In the operating room, while the patient lying down in the operating bed, it is impossible to visualize the patient and the radiological images simultaneously. This scenario can force the surgeon to back-and-forth refocusing, potentially leading to nonoptimal outcomes. BC surgical treatment would benefit from providing real-time availability of threedimensional (3D) representations of the breast and torso’s internal tissues and anatomical structures, including tumor (Fig. 3) [12]. It would enable AR application in BC surgery as a digital and noninvasive guidance system to allow the surgeon to see beyond the patient’s skin and identify with an augmented vision the tumor inside the patient’s breast [12] (Fig. 4). Although promising research has recently been published [10–12], this technology is still immature, with no certified software as a medical device both in Europe and in the USA. But recently, Magic Leap 2® was the first ever AR headset to be certified by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC 60601) to be used both in an operating room as well in other clinical setting to allow critical data and 3D visualization to be integrated into a digital platform.

Current available technology relies on the holographic projection of image medical data in an augmented or virtual world. This means the user needs to manipulate virtual objects (3D reconstructions of CT or MRI data) by hand gestures, which is also the case when using VR. This makes it very difficult to scale as it impairs usability and ultimately results in a poor user experience. The ideal solution would be an automatic AR mode where virtual objects (like tumors) are automatically anchored to the patient’s body. This could be achieved with an advanced computer vision system paired with 3D spatial cameras to accurately scan the patient body and map and recognize activities within the operating room, a state-of-the-art AR/MR setup consisting of a head-mounted display to blend virtual and real objects seamlessly [19], and a highcapacity network (5G) with edge computing to access classified and sensitive image medical data. Building this operating room of the future will require a multidisciplinary collaborative effort of surgeons, medical imaging experts, machine learning and computer vision researchers, and AR/MR and computer graphic developers.

TECHNICAL NEEDS AND LIMITATIONS

Data

The development of a certified hardware and software as medical device capable of displaying electronic medical records and radiological images through an AR headset requires these to be accessible and interoperable. However, even ensuring these two principles, data may still need processing, as is the case of radiological images, where the patient position changes from the acquisition technique to the operating bed. In this case, pose change and other breast distortions (e.g., caused by MRI coils) must be corrected to allow an accurate fusion of the images with the patient body [13]. Additionally, the segmentation of different types of breast tissue (fat, fibroglandular tissue, and tumor) will allow a more accurate AR rendering and subsequent localization of the borders of each tissue. The segmentation process should be automatic with an offline (offline term is used to indicate that the automatic segmentation process is first executed, the results are saved, and later the segmentation results are verified and corrected if needed) inspection and possible curation step. The curated results should be used to train the segmentation algorithms via continuous learning, reducing errors, and the need for curation through time. Additionally, the automatic segmentation process should be robust and generalizable given the variability of acquisition settings and different MRI scanners available.

Real-Time Fusion

To improve tumor localization accuracy, the patient respiratory motion will need to be taken into account to achieve a real-time fusion of the pose-transformed radiological images and the patient. This requires low latency in the complete AR process of real image/video acquisition, most likely being done by multiple 3D spatial cameras, communication to closest data center, processing and return of virtual objects for superimposition [19]. Similarly to AR/VR gamers motion sickness effects [20], these medical applications impose to networking and processing stringent maximum delays. The availability of close (less than 2 ms) powerful computation is required to achieve longer technology usage periods, also contributing to simpler, less powerful end-user terminals, at the same allowing complex data analysis, from multiple sources.

Limitations

Lack of interoperability between healthcare systems hinders the development of the ecosystem to perform 3D live rendering with AR in real time. Current machine and deep learning approaches to analyze radiological images have generalization issues, where changes in the image acquisition protocol or MRI scanner will affect the performance of these algorithms. The new 5G networks can potentially accelerate interoperability between healthcare systems and support AI applications within the virtual health ecosystem [21]. The 5G network architecture will change the future of AI as 5G speeds up cloud services while AI analyzes and learns from the same data faster. However, the efficient use of 5G requires it to be natively integrated in end devices. Unfortunately, new 5G networks have only recently started their implementation process, and careful integration planning on current hospital communication networks is needed for applications such as the presented use case of remote surgical telementoring. Far from being the optimal scenario, the reported solution for surgical remote telementoring provided only 42 ms of RTT (round trip time) to cover a distance of over 900 km (Lisbon to Zaragoza), enough for the proof-of concept showcase and considerably better than other available wireless technologies. Another technical limitation observed was video flickering, a common problem resulting from certain frame rate and shutter speed combinations under artificial lighting, which is the case in the operating room. A possible solution would be to sync led light frequencies between the two surgical light sources in order to improve image quality.

CONCLUSION

Advances in technology brought AR into the health field. We started the introduction of AR in BC surgery with two possible scenarios taking the first steps as experiences that can lead in the future to a widespread use. Both surgical telementoring and impalpable tumors noninvasive localization are two examples that can have success in the future provided the improvements in both data transformation and infrastructures are capable to overcome the current challenges and limitations. A multidisciplinary team composed of surgeons and technological experts is a crucial ingredient to help attain these goals.

STATEMENT OF ETHICS

This study (reference: BCCT.HoloLens) was approved by the Champalimaud Foundation Ethics Committee. Participants’ written informed consent in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration was received. Participants’ written informed consent to publish photos and radiologic images relating to their person was obtained.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Fátima Cardoso reports personal financial interest in form of consultancy role for the following: Amgen, Astellas/Medivation, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, GE Oncology, Genentech, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Iqvia, Macrogenics, Medscape, Merck-Sharp, Merus BV, Mylan, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre-Fabre, prIME Oncology, Roche, Sanofi, Samsung Bioepis, Seagen, Teva, and Touchime. Institutional financial support for clinical trials from the following: Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, Fresenius GmbH, Genentech, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Ipsen, Incyte, Nektar Therapeutics, Nerviano, Novartis, Macrogenics, Medigene, MedImmune, Merck, Millennium, Pfizer, Pierre-Fabre, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Sonus, Tesaro, Tigris, Wilex, and Wyeth. All authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

FUNDING SOURCES

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and study design: Pedro F. Gouveia and Rogélio Luna; data acquisition: Pedro F. Gouveia and Rogélio Luna, Carlos Mavioso, and Rafaela Timóteo; manuscript preparation and editing: Pedro F. Gouveia, Francisco Fontes, Carlos Mavioso, João Anacleto, Rafaela Tim.teo, João Santinha, and Tiago Marques; and manuscript review: David Pinto, Fátima Cardoso, and Maria João Cardoso.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data generated during the current paper are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

1 Eckert M, Volmerg JS, Friedrich CM. Augmented reality in medicine: systematic and bibliographic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019 Apr 26; 7(4): e10967.

2 Ferrari V, Klinker G, Cutolo F. Augmented reality in healthcare. J Healthc Eng. 2019; 2019: 9321535.

3 Gerup J, Soerensen CB, Dieckmann P. Augmented reality and mixed reality for healthcare education beyond surgery: an integrative review. Int J Med Educ. 2020 Jan 18; 11: 1–18.

4 Vavra P, Roman J, Zonča P, Ihnat P, Němec M, Kumar J, et al. Recent development of augmented reality in surgery: a review. J Healthc Eng. 2017; 2017: 4574172.

5 Yang D, Zhou J, Chen R, Song Y, Song Z, Zhang X, et al. Expert consensus on the metaverse in medicine. Clin eHealth. 2022; 5: 1–9.

6 Umphrey L, Lenhard N, Lam SK, Hayward NE, Hecht S, Agrawal P, et al. Virtual global health in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Int J Med Educ. 2022 Aug 31; 13: 230–48.

7 Jin ML, Brown MM, Patwa D, Nirmalan A, Edwards PA. Telemedicine, telementoring, and telesurgery for surgical practices. Curr Probl Surg. 2021; 58(12): 100986.

8 Bilgic E, Turkdogan S, Watanabe Y, Madani A, Landry T, Lavigne D, et al. Effectiveness of telementoring in surgery compared with onsite mentoring: a systematic review. Surg Innov. 2017 Aug; 24(4): 379–85.

9 Hamdi M, Van Landuyt K, de Frene B, Roche N, Blondeel P, Monstrey S. The versatility of the inter-costal artery perforator (ICAP) flaps. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006; 59(6): 644–52.

10 Perkins S, Lin M, Srinivasan S, Wheeler A, Hargreaves B, Daniel B. A mixed-reality system for breast surgical planning; 2017.

11 Duraes M, Crochet P, Pages E, Grauby E, Lasch L, Rebel L, et al. Surgery of nonpalpable breast cancer: first step to a virtual per-operative localization? First step to virtual breast cancer localization. Breast J. 2019 Sep; 25(5): 874–9.

12 Gouveia PF, Costa J, Morgado P, Kates R, Pinto D, Mavioso C, et al. Breast cancer surgery with augmented reality. The Breast. 2021 Jan 27; 56: 14–7.

13 Bessa S, Gouveia PF, Carvalho PH, Rodrigues C, Silva NL, Cardoso F, et al. 3D digital breast cancer models with multimodal fusion algorithms. Breast. 2020 Feb; 49: 281–90.

14 Kopans DB, Swann CA. Preoperative imaging-guided needle placement and localization of clinically occult breast lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989 Jan; 152(1): 1–9.

15 Dash N, Chafin SH, Johnson RR, Contractor FM. Usefulness of tissue marker clips in patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999 Oct; 173(4): 911–7.

16 Rose A, Collins JP, Neerhut P, Bishop CV, Mann GB. Carbon localisation of impalpable breast lesions. Breast. 2003 Aug; 12(4): 264–9.

17 Gray RJ, Salud C, Nguyen K, Dauway E, Friedland J, Berman C, et al. Randomized prospective evaluation of a novel technique for biopsy or lumpectomy of nonpalpable breast lesions: radioactive seed versus wire localization. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001 Oct; 8(9): 711–5.

18 Sajid MS, Parampalli U, Haider Z, Bonomi R. Comparison of radioguided occult lesion localization (ROLL) and wire localization for non-palpable breast cancers: a meta-analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2012 Jun 15; 105(8): 852–8.

19 Navab N, Martin-Gomez A, Seibold M, Sommersperger M, Song T, Winkler A, et al. Medical augmented reality: definition, principle components, domain modeling, and designdevelopment-validation process. J Imaging. 2022; 9(1): 4.

20 Pettijohn KA, Peltier C, Lukos JR, Norris JN, Biggs AT. Virtual and augmented reality in a simulated naval engagement: preliminary comparisons of simulator sickness and human performance. Appl Ergon. 2020 Nov; 89: 103200.

21 Aerts A, Bogdan-Martin D. Leveraging data and AI to deliver on the promise of digital health. Int J Med Inform. 2021 Jun; 150: 104456.